A Changing National Identity: Anzac Day 2014 and Memories of my Irish Ancestors.

I wonder how many descendants of Irish convicts fought for the British Empire in the Boer War and subsequent World Wars and how the issues of ethnic and cultural difference shape our nation today.

When discussing the oral transmission that has preserved the traditional, Celtic music of the British Isles, Jordi Savall[1] said:

Just as the face is the mirror of the soul, a people’s music is the reflection of the spirit of its identity, individual in origin but taking shape over time as the collective image of a cultural space that is unique and specific to that people.

This will not happen in the New World countries, such as Australia, a nation made of many cultures and races. However, the passing down of each history, be it orally, as in the case of Celtic music, or written, as Savall says:

These processes of transmission are also paths of evolution, innovation and, therefore, paths of transformation by which they undergo the diverse influences of other musical styles that are foreign, modern, or even very remote in origin, resulting in new and equally legitimate forms of interpretation.

[1]Savall, Jordi, Frontfroide Abbey [France], 29th July, 2010.Translated by Jacqueline Minett. [copied from the booklet in the CD, The Celtic Viol II: TrebleVviol and Lyra Viol.Alia Vox, AVSA 9878.]

Up until November 2013, I had flatly denied having any convict blood. Not because, like some, I was embarrassed by the “stain”, but wholly due to my ignorance and perhaps that of previous generations. The following is a story of many unanswered questions.

My mother was born Inez Patricia de Valera Connolly in 1921 at Enfield, Sydney, in the first year of the Irish Free State. Keen to discover her ancestral story, in 1995 she and I ventured along the Great Western Highway across the Blue Mountains in the quest for her people. We found a few graves and evidence that an unknown cousin had previously visited the Lithgow and District Family History Society.

However, without the internet as a powerful research tool to facilitate both church and state record keeping, we came to a dead end, in the “dead centre” of the mid-west town of Wellington, the birth place of her maternal grandmother, Ellen Crane.

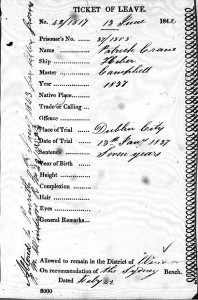

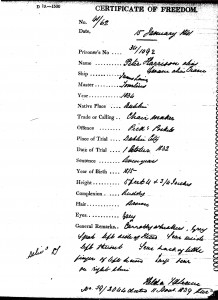

Ellen’s father Peter Crane arrived in Sydney in 1834 on the convict transport the James Laing, a horrid voyage by all accounts. His brother arrived brandishing the same costume and accessories in 1837 on the Heber. At this stage, it appears that they were orphaned, as no names are given for parents on any documents, always marked “unknown”. Both boys were in their teens when arrested in Dublin and were incarcerated in Kilmainham Gaol before being sent to the penal colony of NSW; Peter’s crime “picking-pocket’” and Patrick stealing a “kerchief”. No doubt, just two more underlings removed from their homeland to make room for the avaricious, colonial oppressor.

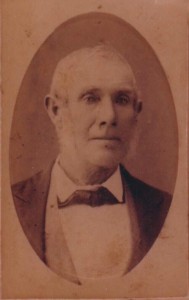

Ellen’s mother, Mary Cassidy from Ballinagar, Derry, may also have been orphaned. Judging by her photo, magically conserved by the Wellington Historical Society, she appears to wear the attire of a maid. She arrived via Plymouth on the Thetis in 1848, possibly from the work house under the programme set up to provide service workers for the squattocracy and other wealthy colonialists. Mary Cassidy married Peter Crane the emancipated convict at St Michael’s Kelso in 1851 and they soon set about acquiring property and producing a large family at Wellington, NSW.

Strange as it may seem, their daughter, Ellen Crane, had two grandsons who enlisted in the RAAF in 1942 and eventually played a role in WW2 in the English RAF to subdue the Nazis. These were Darrell and Hilary Connolly, one of whom a bombardier in Lancasters, never returned to his fledgling nation.

In 1885 Ellen Crane married Stephen Joyce a labourer from Galway, Ireland, who entered the NSW Police Force in 1881. Their daughter Mary married Michael James [Jim] Connolly in Lithgow in 1908.

In November 2013, I was reading Robert Hughes’s The Fatal Shore, when arriving at the chapter describing the journeys undergone by convicts and masters, The Voyage, and as synchronicity will have it, I received an email on that same day from a distant and lost Lithgow cousin, descendant from the same Bathurst Connolly family, who informed me that our first Connolly relative was a convict Owen Smyth, arrested in Monaghan for “riot and assault”. Owen was moved to Kilmainham Gaol in Dublin and luckily, escaped the gallows, being transported on the Clyde in 1838 to Bathurst Gaol. I had just read the details of this transport in The Fatal Shore; the Clyde had set sail for NSW with 215 Irishmen on board.

Owen Smyth is classified as a “Whiteboy” in Peter Mayberry’s Irish Convicts to NSW, in which he indicates if a convict was a rebel and under which category. “Whiteboys” can be viewed in two ways, violent thieving criminals or brave, righteous, freedom fighters, depending upon which side of the colonial fence you sit. They were mostly farm labourers, many of whom once descended from great Irish families who had sovereignty over that land. After various confiscations and clearances by the British – a punishment for their religious affiliations, they were left with tiny plots of what were often arid land, where they were permitted to grow potatoes for themselves and family. Many toiled for the land lords, eking out a miserable existence. If the potato crop failed, they starved, as much of the food produced on the land that was once their own, was now exported to the coffers of the English aristocracy. What would one do in such a situation?

Was this rebellious and ant-colonial sentiment passed down to my mother? It certainly was, as Inez often expressed her dislike for royalty and our links to England. She was not bigoted; as in the true spirit of the new nation, Inez had friends from many ethnic origins, including English and German. I ask myself just what did she really know and what spirited her disgust toward Australia’s mother-and-daughter relationship with England.

Why did we lose contact with our Connolly relations who had their pioneer foundations in the Bathurst and Wellington regions of the NSW central west? Owen Smyth, the convict, was sent to Bathurst Gaol from the Clyde and after receiving his Certificate of Freedom, he settled in that region, eventually using his savings to open a small business. Was it luck or just hard work that allows him to sponsor the immigration from Monaghan Ireland of his sister Mary, her husband Patrick Connolly and their five children on the Commodore Perry in 1856? There are many unanswered questions, but after browsing through convict files of Connolly folk from Monaghan, who were sent to Van Diemen’s Land, the story is vastly different. Luck would have it that Owen was sent to Bathurst, at that time. The rest is history, a very good history. This Connolly/Smyth family had an impressive list of businesses that were part of the stoic, hardworking, communal spirit that built these magnificent towns of the inland.

Did Owen impart his story over and over again around the kitchen table? Certainly, the rebellious baton, or should I say what seems to be an instinctual fight for basic human rights, was passed down the line to my grandfather Michael [Jim] Connolly, the son of Owen , the son of Mary and Patrick Connolly.

M.J Connolly must have been confident and clever as he became manager of large general stores in Gulgong and Mudgee and may have operated a wine and spirits store in Lithgow. Nevertheless, things turned sour for him and his young family at Lithgow during the time of WW1.

At this time about one third of the Australian population was Irish and the sense of another identity, apart from being a subject of the British throne, pervaded much of the country, the now federated states of a new Australian nation. A new national identity was forming or fomenting, as some may see it, but the idea of self-determination and a “fair go” for the Irish non-conformists who were culturally mostly Catholic. Even if lapsed Catholics, the notion of fighting for Britain, the nation that had occupied Ireland, their homeland, for almost 800 years, was likely to cause some level of defiance and unrest.

When I knew him, my grandfather M.J Connolly [Jim] was beyond communication and I was too young to engage in such a dialogue. I will never know the true details of this story. Nonetheless, when he and Mary lived at Lithgow in the second decade of the twentieth century, a small arms factory had been built there and during wartime, provided much employment for the locals.

You can draw your own conclusions about Inez, my mother, and how she may have responded to the research about her ancestors. I know that I have a deep and ever-growing affection for them. I remember them every day, and am grateful to them for the fortune of my existence. However, I am aware that their good fortune and my own were and are at the expense of the people of the first nation of this arcane continent. I only hope that none of my kinfolk were directly involved in any violent or other malevolent action that led to much misery of these people, some of whom shared wretchedness, not dissimilar to that of the dispossessed Irish. I know many of us did profit from living on stolen land as we all do in the continuum to this day.

Of course, no matter from which country you originate, as an Australian citizen, when England was at war[and so often], you were automatically a subject of the British Empire and this is the quandary in which Irish Australians found themselves at the outbreak of WW1 and for that matter, the Boer War.

To be sure, many people of Irish blood had forgotten their roots and the past issues of oppression and dispossession had been airbrushed from their memories, along with language and other codes of cultural identity. Not my grandfather “Jim”. As my cousin Terry Connolly and I remember, without much detail, there was something about a “white feather” in connection to the Lithgow small arms factory. It seems M J. Connolly [Jim] found he was not welcome in Lithgow and he and Mary uprooted their family “across the divide” to Sydney. Jim had received a white feather in his letter box from angry, local residents.

He was possibly an anti-conscriptionist. After all, in the wake of the Irish born Daniel Mannix, Archbishop of Melbourne, he and many others could not concede to sending our young men so far away, fighting a war for the nation that still occupied their homeland; a war inflamed by a squabble over territory perpetrated by greedy, ignorant hegemonic “aristocrats”, of some consanguinity. So, many of our young beauties died needlessly in that diabolical war.

My mother once revealed to me that her father M. J. Connolly [Jim] read Carl Marx, enjoyed red wine and was an atheist. He had certainly jettisoned his Catholic cloak. Rod Parkes, my distant cousin who is completing the Connolly family research, explained something about the attitude of the Lithgow locals, “It seems at odds with the attitude of the general public feeling of ant-conscription which had apparently been put to a plebiscite twice and defeated twice.”

If “Jim” Connolly was anti-conscription or merely anti-war or English alliance, due to his knowledge of Irish history, then he found himself much alone in Lithgow at the time. If he received the white feather, then it was time to uproot the family for their safety. Hence, the chasm rips away the kinship and family history of pioneer and convict roots. The people of Lithgow, needed employment, and now boom times were facilitated by a war

.

“Jim” was a consciousness objector, not just a pacifist, but took action for a complex set of reasons. Terry Connolly his grandson, enjoyed a long and rich career as a Hercules pilot in the RAAF. His older brother, Jim Connolly also joined the armed forces. Ironically, he was the first Duntroon graduate to receive both the Queen’s Medal and the Sword of Honour. I remember the huge photo on the front page of The Australian. James Michael Connolly received these symbols of valour and virtue from “Sir” Paul Hasluck, the incumbent Governor General. James Connolly later played an active role in the Vietnam War, another story of chagrin, remorse and loss.

No doubt, one can assume that the father of Terry and Jim Connolly, Hilary, was the young son of Michael and Mary Connolly who did return from the killing fields of Europe. He and his brother Darrell were already graduates from Sydney Teacher’s College and had completed their high school at Holy Cross College Ryde in Sydney, continuing the Irish Catholic tradition. Like other ethnic groups in Australia, for a few generations, it is religious and cultural ties that maintain the identity of the heritage they leave behind. For some it gradually fades away. This is both a regretful loss and a healthy navigation toward a new and unified nation. Some would say it softens the “tribal” element that encourages divisiveness in a community and the wider world: the stuff of wars

.

Many of us mourn for our rich past and I for one, feel the need to dig deeply for my ancestors for that is who I am. On the other hand, it is a meshing of the elements of this historical discourse that are what the nation is today, thus the need for a lively debate at all times. Believe it or not, some of us still live in a community of humans in nature not just an “economy”. Social divisions defined by money, could also be termed “tribal” if we wish to continue this interchange, but it could become messy and embarrassing. Nonetheless, it is relevant to the discussion of fostering a healthy society.

Our national identity is in a constant state of flux, like the global village, the populations are shifting like the sand. Consequently, the national identity is part of a world-wide continuum fluctuating from its colonial underpinnings, with a first nation always there in the background and increasingly in the foreground, which ought to be respected and observed as an anchor and benchmark upon which to build a new third nation, one that is essentially restorative with respect to past ills and the destruction of the environment.

Sadly, missed by my generation, Darrell Connolly, the son of Michael [Jim] Connolly of the white feather, was the son who did not return to his antipodean home. I knew from conversations I shared with my uncle Hilary Connolly that he never recovered from this loss. My mother spoke of their closeness, the wild fights, their love for cricket, football, athletics and music. Clearly now, the photos we recovered convey their very different dispositions. Hilary was quiet, pursuing a long career as a primary school teacher and principal who in that Australian spirit of a ‘fair go’, set up a night school for parents of immigrant children in the western suburbs of Sydney, in order to facilitate their English language acquisition. Hilary maintained his love of sport throughout his life and refused to leave the house if the cricket was being transmitted on the TV.

We have a rough-cut gramophone recording of Darrell Connolly, his brother, sending his Christmas greetings to family and sweetheart describing visits to tourist spots in Canada and the US, before he departed to Europe in 1943.He has that unmistakeable voice of the mid twentieth century Australian vernacular.

I once saw the letter sent to inform his parents of the retrieval of his body from Kiel Harbour in Northern Germany. I have also seen the flying record and bombing history of both brothers, compiled by Terry Connolly, son of Hilary who was repatriated to Australia toward the end of the war.

I recently spoke to a German family whose innocent relatives were wiped out in one of these bombing raids. The aftermath of WW1, when the evil perpetrators of horror rose to power in Germany, dragging so many into abject poverty, loss, torture and death in WW2, is a time that needs to be rigorously scrutinised, because punitive action taken by the victorious allied forces might have been avoided to mitigate a possible reaction of circumstances, which ultimately lead to the rise of a psychopath. Such a stream of events leading up to and post 9/11 has led to current woes and a world frightened to look at itself and reflect, asking the question “why”?

I am essentially a pacifist, but also a realist. The cliché, “history repeats itself” echoes loudly, as avarice, inherent to human nature, prevails. While I do not glorify war in any way, and find it increasingly irritating that various Australian Prime Ministers such as John Howard and his protégé Tony Abbott continue to promote an unhealthy jingoistic nationalism as they purloin the Anzac platform to push their brand of corny, anachronistic Aussie-aussie -aussie- ism, they send the wrong message. In fact, they have completely missed the message of the Anzac legend.

The impetus that increasingly swells the crowds attending Anzac ceremonies is not about being an “Aussie”, or the tragedy of losing an inglorious battle, but rather, it is about remembering our courageous men and women who sacrificed their lives in a stupid, unknown territory, needlessly harming others of their ilk, due to the mismanagement of ignorant, arrogant, incompetent, imperialist buffoons.

How some of us cringe today as Tony Abbott brings back the medieval, nepotistic practice of peerages that go hand-in-glove with oligarchies. Can you afford one? Our PM doesn’t seem to understand the Australian people or the history of the national identity, a topic which deserves a lengthier discussion than I can afford here. We are all boat people, Mr Abbott, including you of the short memory: show some compassion.

Rather, the sacrifice of the Anzacs and all other soldiers who have fought in wars, ought to be utilised as a bench mark through which Australians are enabled to observe the positive and negative aspects of our past, honour the people of the First Nation and the war they found themselves fighting from 1788 to protect their country, and embrace a future whose principles are grounded in respect for all others and the beautiful planet that allows us to live and breathe.

I do attend the dawn service, not to glorify war, or subscribe to this new and vulgar brand of oink-oink nationalism, but to honour the memory of my beloved, strong, brave father and uncles. Even the war with the Japanese, my father’s war, was a reaction to the imperialism and racism of western, white colonial powers.

For Darrell Connolly, the more extroverted of the brothers, also brave, handsome and strong, we regret not knowing you and hope soon to visit your final resting place in Germany.

My father’s people, James McHugh and Anne Casserley, left Ireland in the 1870s, for equally dismal reasons. Their stories and those of all my ancestors and many of yours, if hailing from the continually expanding Irish diaspora, will be treated in a book I hope to complete in the near future.

Jules McCue April 2014

My unknown uncle, Darrell Connolly, died over Kiel Harbour on 26th August 1944, a bombardier in a Lancaster on his 11th mission with the RAF 100 Squadron.

My uncles, Darrell [left] and Hilary Connolly [middle] photographed at a cricket game. Hilary served in the 77 Squadron of RAF Bomber Command as a bombardier in four-engine Halifax bombers, returning to a career in school teaching and raising a family.

My grandfather, Michael James [Jim] Connolly, the father of Darrell and Hilary. He received a white feather whilst living in Lithgow at the time of WW1.

My great Grandfather Owen Connolly, great grandmother Bridget and daughter, the parents of Michael James Connolly [Jim]. He and his family [parents and sibblings of Owen] were sponsored by his ex-convict uncle Owen Smyth, “Whiteboy”, migrating at age 9 on the Commodore Perry, 1856, settling in the central west of NSW.

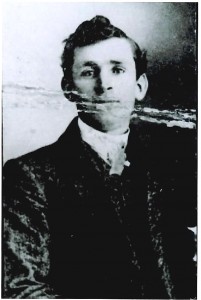

My great, great grandfather, Peter Crane, arrived as a convict from Dublin on the James Laing in 1834 and settled in Wellington, NSW.

My great, great grandmother, Mary Crane nee Cassidy, arrived from Derry in 1848 on the Thetis.

My great grandmother, Ellen Joyce, nee Crane married Stephen Joyce from Galway in 1885. After his early death, she moved from Blackheath to Thames St, Balmain, near the wharf.

Patrick Crane’s [great great uncle], Ticket of Leave

Patrick Crane’s [great great uncle], Ticket of Leave

Great great grandfather Peter Crane’s Certificate of Freedom

Great great grandfather Peter Crane’s Certificate of Freedom